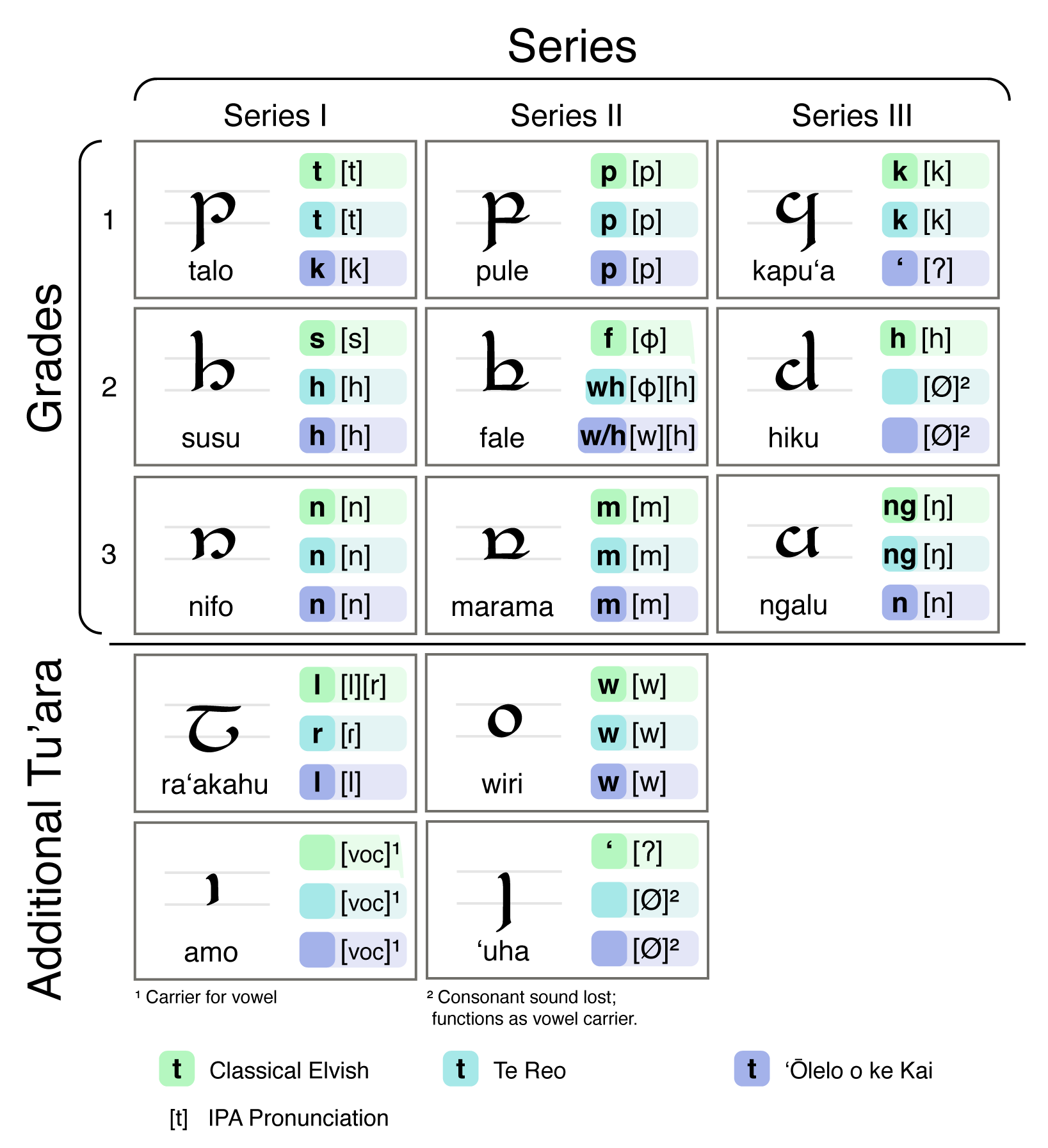

Tengwar for Te Reo

"My language is my treasure and my prized ornament."

This page describes a counter-factual in which the Tengwar writing system (from Tolkien's Middle-Earth) is instead a native writing system—called Tuʻara—developed by speakers of Polynesian languages.

I developed it primarily for use in my D&D game. I use real world languages, but often remixed with different writing systems (and different histories of contact). In this world elves use Austronesian languages: the most commonly encountered group of elves use Te Reo (Māori), and the second most common elven language is ʻŌlelo o ke Kai (Hawaiʻian).

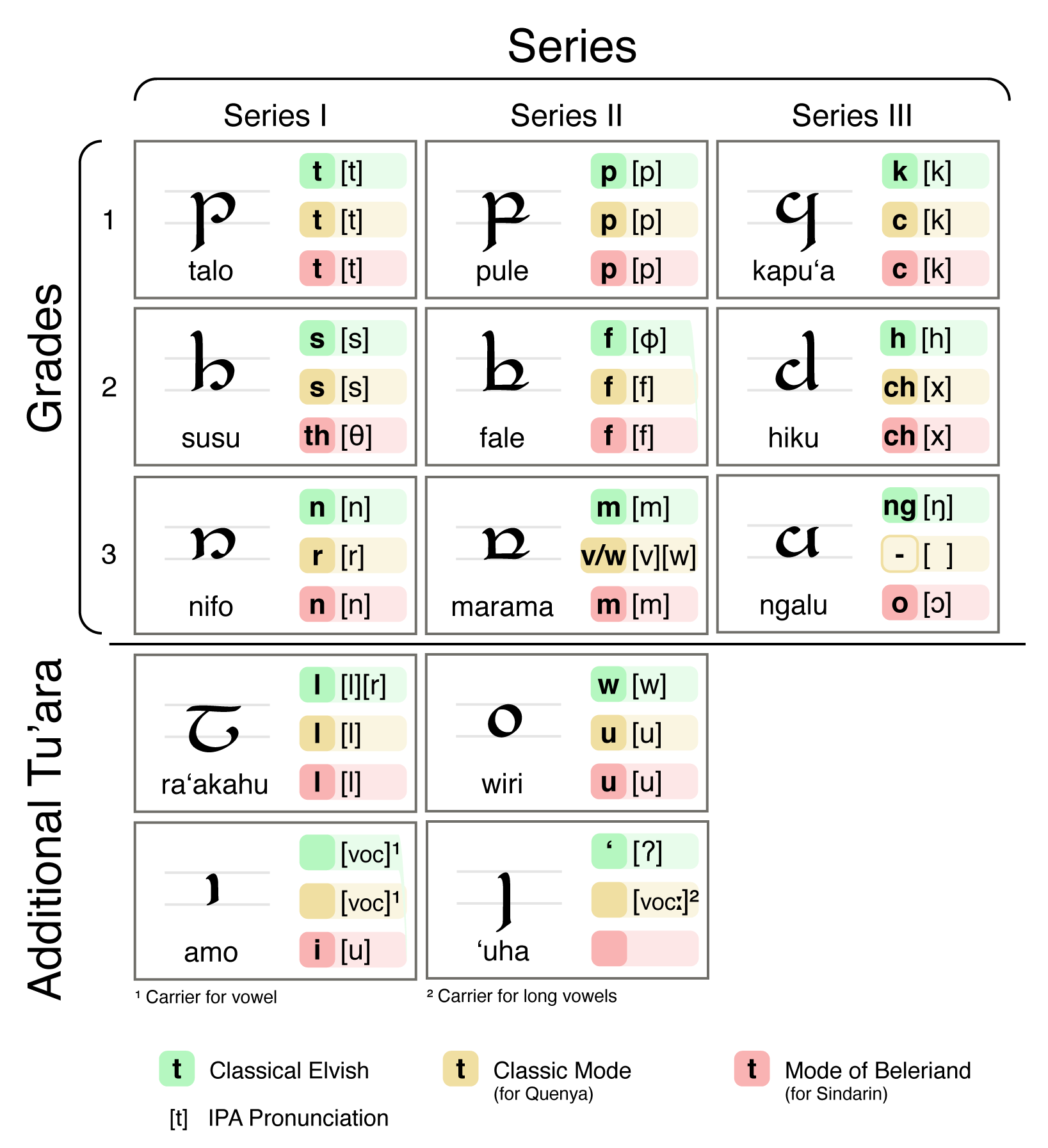

The Tuʻara

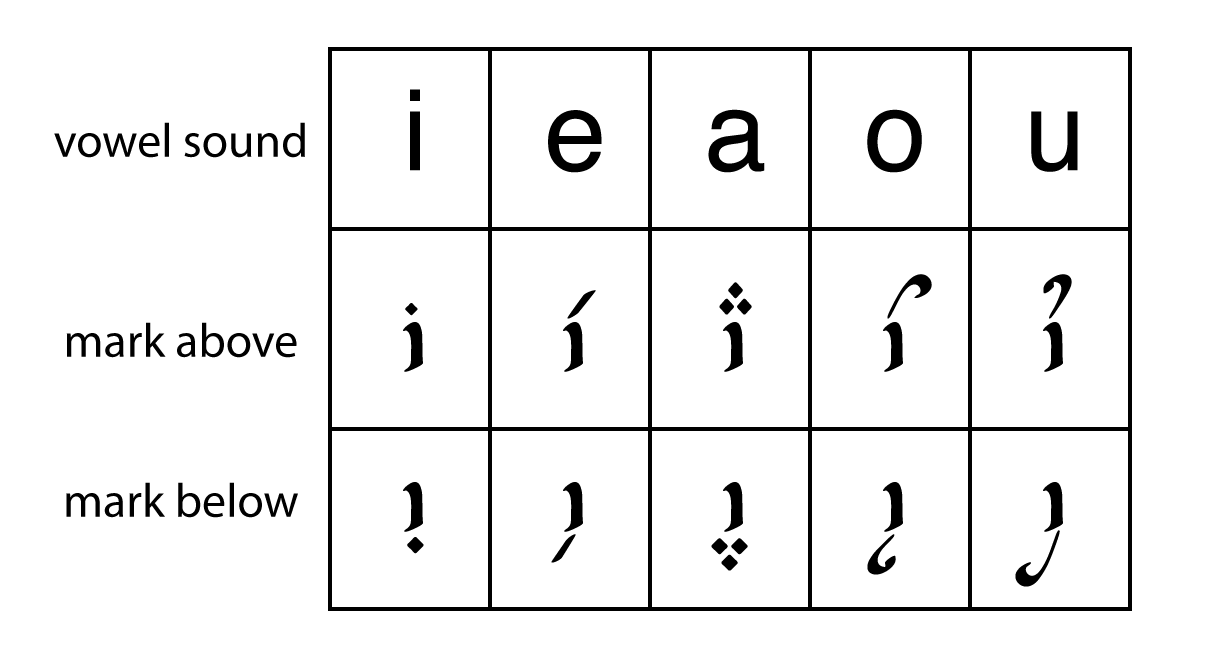

Tosu horo (vowel marks)

By the time of Classical Elvish, vowel marks had developed. The amo vowel carrier was introduced at the same time. Vowel marks can be placed either above or below the preceding consonant, with the position determined entirely by aesthetics.

There are various modes of marking vowels: now vowels can be marked, all vowels can be marked, or vowels other than a can be marked (abugida-fashion).

The mode used on this page is with a left unmarked. Certain common short words are also left unmarked for vowels even though it is not an a, most notable t on its own is understood to be te: "the", not ta. (Though in ʻŌlelo o ke Kai the definite article is pronounced with either e or a depending on the beginning of the next word).

Origins (Internal History)

"As though it were a spider's web!"

Tuʻara was developed by elves after early contact with giantish writing in the distant past. One of the commoner mediums of giantish writing at the time was giantish rune-bones, thus the name Tuʻara, from an archaic word meaning "bone".

(I derived it from Proto-Austronesian *CuqǝlaN: "bone", which has no real life reflexes in Polynesian languages because it was replaced by iwi as the word for "bone" in Polynesian—from Proto-Austronesian *duʀi: "thorn".)

The elves probably could not read giantish writing at the time, but they observed the principles, and created their own writing for their own language.

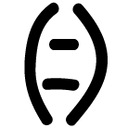

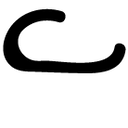

The final result of this development was an abjad-like system with consonant letters derived from archaic pictographs using an acrophonic principle: each letter is used for the consonant at the beginning of the word illustrated by the pictograph it is derived from.

* Pre-Classical Elvish distinguished the r and l sounds, but they had already merged by even the earliest Classical form of the language. The early development of tuʻara shows some sporadic distinction between r and l sounds, but nothing was ever standardized.

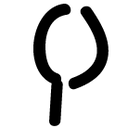

** The letter amo was added after the rest of the consonants and, unlike the rest, was not named acrophonically—in the older forms of Classical Elvish amo: "carrier, shoulder-pole" was pronounced with a glottal stop (ʻuha) at the beginning. But in later Classical Elvish, the Classical glottal stop was already lost in many cases, and amo was interpreted as if it was acrophonic like the rest and is now spelled without the ʻuha.

Elven Terminology

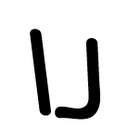

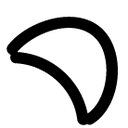

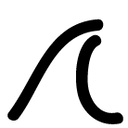

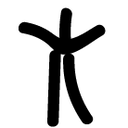

| Classical Elvish | Te Reo Elvish | ʻŌlelo o ke Kai Elvish | Meaning | Tuʻara |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Te Leo Matuʻa | Te Reo Matua | Ka Leomakua | "The Elder Speech, Classical Elvish" | |

| Tuʻara | Tuara | Kuala | "writing, the elvish script, a letter" | |

| Tosu horo | Tohu oro | Tohu oro | "vowel mark" | |

| Talo | Taro | Kalo | "taro (root)" (letter name) | , |

| Pule | Pure | Pule | "cowrie (shell)" (letter name) | , |

| Kapuʻa | Kapua | ʻApua | "cloud, fog" (letter name) | , |

| Susu* | Huhu* | Huhu* | "breast"* (letter name) | , |

| Fale | Whare | Hale | "house" (letter name) | , |

| Hiku | Iku | Iʻu | "(fish) tail" (letter name) | , |

| Nifo | Niho | Niho | "tooth" (letter name) | , |

| Marama | Marama | Malama | "moon" (letter name) | , |

| Ngalu | Ngaru | Nalu | "wave" (letter name) | , |

| Raʻakau | Rākau | Lāʻau | "tree" (letter name) | , |

| Wiri | Wiri | Wili | "drill, bore" (letter name) | , |

| ʻUha | Ua | Ua | "rain" (letter name) | , |

| (ʻ)Amo** | Amo | Amo | "carrier, support post, shoulder-pole" (letter name) | , |

* In both of the modern languages, the word for breast is "Ū", with the two syllables collapsed into a single long vowel, but the letter is still called "Huhu".

** See note on previous table regarding the glottal stop/ʻuha at the beginning of amo.

Development Story (External History)

"A day to break the spade."

I have a D&D setting I have developed, "Tegurala". When I started working on it, I decided to use real world languages for the fantasy languages, for naming language consistency without having to create a bunch of new conlangs. One of the first languages I picked was to use Māori for the Elven language. I've since expanded that to more general elves use Austronesian languages, but in most cases the Māori-speaking are most often encountered. (I've developed other groups of elves who speak Hawaiʻian, Rapa Nui, Malay, and Ilocano.)

And of course, Elven needs its own native writing system, which Māori doesn’t come with. One of my original players lobbied me to use the Tengwar. While I had ruled out using Quenya or Sindarin for the language, using Tengwar seemed a reasonable compromise.

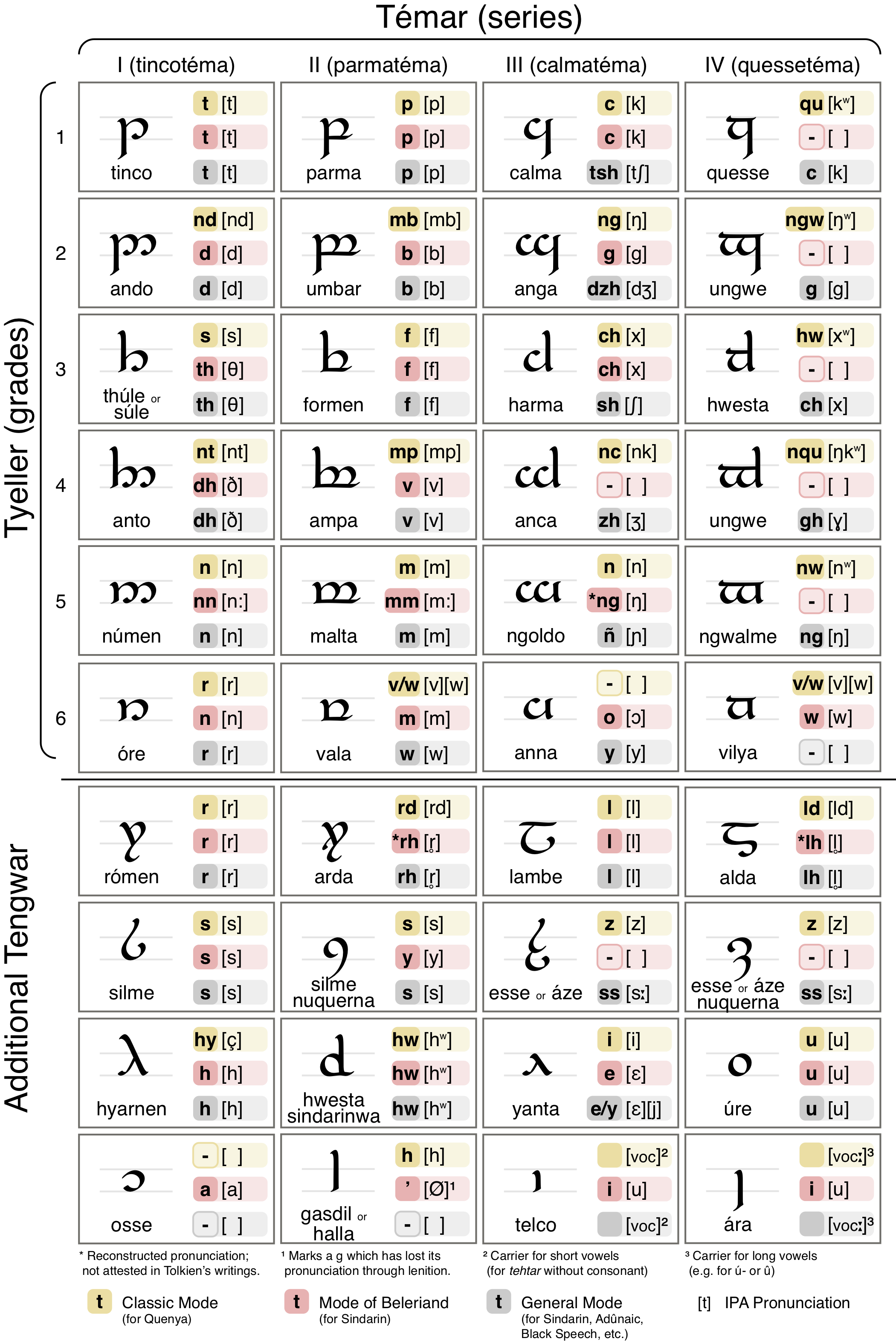

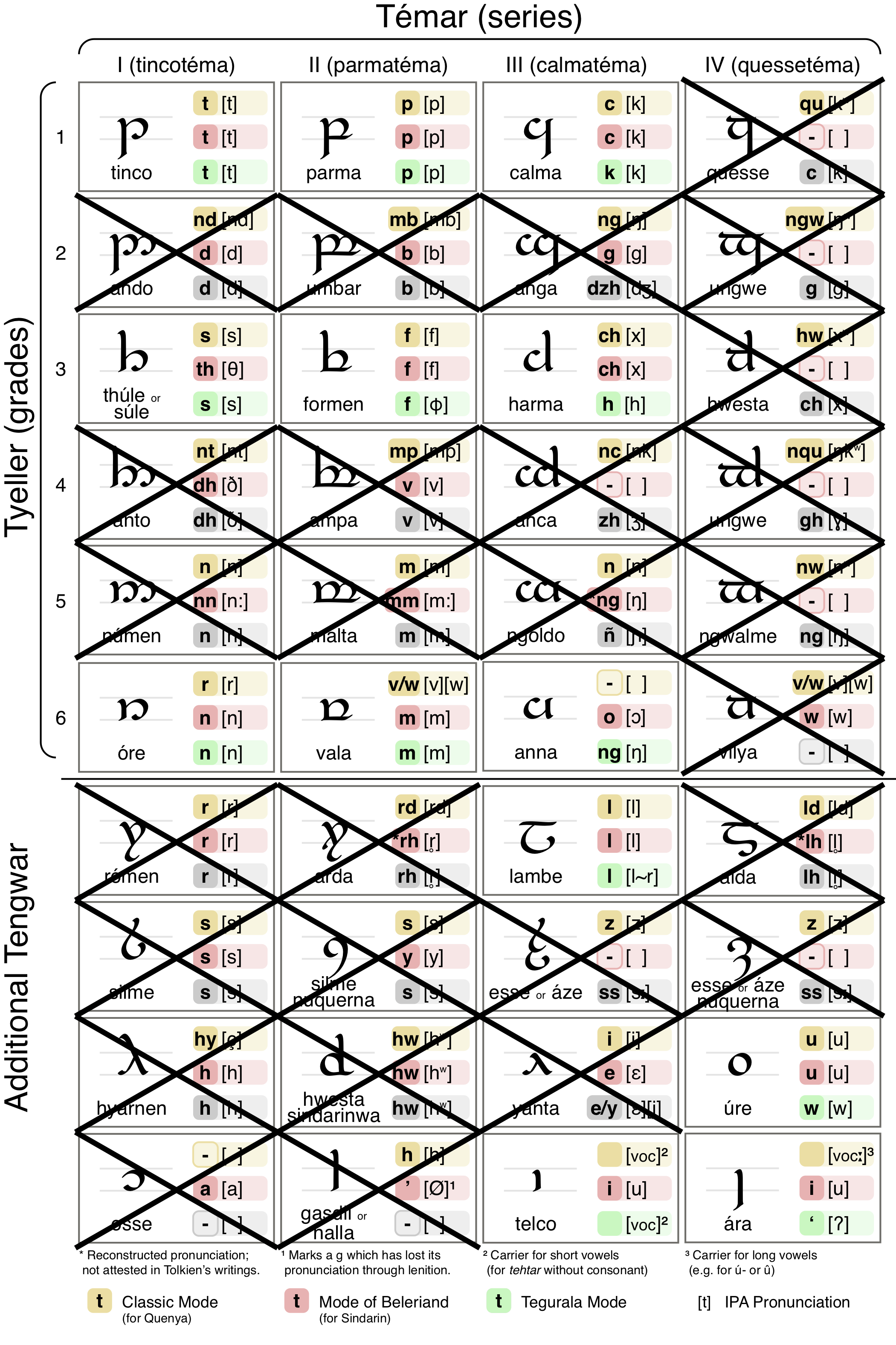

The majority of the Tengwar are part of an ordered table. For example Series II are the labials (and labiovelars), or Grade 5 are the nasals; the shapes of the glyphs are likewise featural: Series I glyphs have downward-facing, open bows, Grade 2 glyphs have double bows and descending stems. Since I wanted Tegurala tengwar to represent a writing system native to the language, not borrowed from another language, I needed a system that used as coherent a pattern as possible selected out of full Tengwar.

The consonant inventory of Māori is: /p/, /t/, /k/, /ɸ/, /h/, /m/, /n/, /ŋ/, /ɾ/, /w/. At first glance, this would use:

- Grade 1: Series I-III

- Grade 3: Series II&III

- Grade 5: Series I-III

- Grade 6: possibly Series I and/or IV

- or rómen and úre from the Additional Letters

- The short and long carriers, for vowel-initial syllables.

That approaches a coherent subset. Four letters from the Additional Letters, plus get rid of Series IV, and Grades 2, 4, and 6, use everything else. It leaves only a gap at Grade 3, Series I (súle). You could move /w/ or /ɾ/ to that glyph, from out of the additional letters, but neither makes phonetic sense in that position.

Using Grades 1, 3, 5 is a little weird based on glyph shapes, since Grade 5 glyphs are the double-bow version of Grade 6 glyphs. But if we slip a little influence in from the Beleriand Mode (that is, Sindarin Tengwar), we can just use Grade 6, I-III for the nasals instead of Grade 5 I-III. This eliminates all double-bowed glyphs, simplifying subset.

So anyway, I got to this point fairly rapidly, and said, “Well, that’s reasonably good, if not perfect.” But then I had an intuition that if I based the orthography on Proto-Polynesian or Proto-Eastern-Polynesian, it might work better.

And it did, it came together wonderfully!

Not only does this give a better fit than the Māori inventory, it also gives the orthography with built-in history: the words are being spelled as they were pronounced in an implied Classical Elven, at least a thousand years ago (times whatever multipliers you care to add for the counterfactuals in the game world version of the language, such as being spoken by elves instead of humans).

Quick transliteration guide

Elven orthography represents not the current pronunciation of words, but the pronunciation in an older period, from which the spellings have been preserved (the same is true of English, and many other languages that have been written for at least several hundred years). The part of Classical Elvish (Te Leo Matuʻa) is played by Proto-Polynesian (or more accurately, a form somewhere between Proto-Polynesian and Proto-Nuclear-Polynesian).

Luckily, it is pretty easy to reconstruct a Proto-Polynesian word from a Māori word, except for a couple of mergers. In the case of these mergers, we can pretend modern elves also have trouble spelling the old forms, and pass off our mistakes as authentic!

Mostly these days I have enough knowledge and resources for Polynesian historical linguistics that I can quickly look up the actual Proto-Polynesian reconstruction to base the tengwar spelling on. But for those who don't have that, here's my simplified method for transliterating a known written Māori word into Tuʻara that I originally used, and still do when I don't have a reconstruction available.

Vowels

Vowels are simple. They are marked above or below the preceding consonant (the consonant of the same syllable), exactly the same as the Mode of Beleriand. The five simple vowel marks of Tengwar map directly to the five short vowels of Polynesian languages. In some hands, vowels are often left unmarked if they are short /a/ or in the case of certain common particles like te.

Māori long vowels and diphthongs are usually the result of consonant deletions between two originally separate vowels. Handling of these is described in the Consonants section. Other than that, If you assume the Proto-Polynesian vowels of a word are the same as in Māori, you'll usually be right.

Māori and Hawaiʻian vowels are usually the same, so you can use the same method for Hawaiʻian words.

Consonants

- Māori t, p, k, n, m, ng, and r are easily transcribed as the corresponding Tuʻara (talo, pule, kapua, nifo, marama, ngalu, and raʻakau).

- Māori w is written wiri.

- Māori word initial wh is written fale.

- Māori word initial h is written susu.

- Māori word internal h may correspond to either Te Leo Matuʻa fale or susu—I default to susu if I don't know the protoform.

- Māori long vowels and dipthongs are written as two vowels with a ʻuha or hiku (Classical Elven /ʔ/ and /h/ respectively, both now lost) inserted “between” them, i.e. carrying the second vowel. I default to ʻuha for long vowels and hiku for dipthongs if I don't know the protoform.

- Māori words initial vowels can be carried by amo (if it began with a vowel in Classical Elven) or ʻuha or hiku. I default to hiku, but I try to mix it up with at least some amo.

ʻŌlelo o ke Kai Consonants

Hawaiʻian (ʻŌlelo o ke Kai) is slightly harder, because it has a few more sound changes than Māori from Proto-Polynesian, including two more mergers. When transliterating a Hawaiʻian word without reference to a Māori cognate or a Proto-Polynesian reconstruction, I use the following steps:

- Hawaiʻian p, m, l are transcribed as the corresponding Tuʻara (pule, marama, and raʻakau).

- Hawaiʻian k is written talo.

- Hawaiʻian ʻ is written kapua.

- Hawaiʻian n can correspond to either nifo or ngalu.

- Hawaiʻian h can correspond to either fale or susu.

- Hawaiʻian w can correspond to either wiri or fale.

- Hawaiʻian dipthongs and long vowels are handled the same as Māori.

- Hawaiʻian words initial vowels are handled the same as Māori.

Advanced Complications

There are a few cases in which the basic rules I outlined above can be improved, when I'm spending more time with a specific word. Feel free to skip this part.

Advanced Vowels

I said Māori long vowels and diphthongs are usually the result of consonant deletions. The most common cases in which they are not are: 1. Long vowels: Māori words that are not particles are phonologically required to be at least two morae, but that doesn't seem to have been true in Proto-Polynesian. So in a Māori word that is one syllable with a long vowel (e.g. whā, "four"), the long vowel could be from lengthening to meet the minimal word requirement, instead of from consonant deletion (in the example, from Proto-Polynesia short *fa, "four"). 2. Diphthongs: some Proto-Polynesian words did have sequences of vowels (assumed to be separate syllables with hiatus rather than diphthongs yet) as a result of an earlier consonant deletion from Proto-Austronesian to Proto-Polynesian, which became diphthongs in Māori.

There are the same complications for Hawaiʻian, plus be careful of /o/s, especially near the beginnings of words. The most common vowel change is Hawaiʻian /o/ or /ō/ from Proto-Polynesian /a/, and it is often triggered on a root-initial /a/ by adding a prefix. Additionally, there is a very common prefix hoʻo- (and its many variants, which I happen to have written an undergrad paper on), which is from Proto-Polynesian *faka (and is spelled in Tuʻara accordingly). Another common Hawaiʻian vowel change is /a/ from Proto-Polynesian /e/.

Advanced Consonants

Most of the cases in which the Te Leo Matuʻa spelling is ambiguous from the Māori, it can be resolved by finding either a Proto-Polynesian reconstruction; or a Tongan cognate, since Tongan preserves Proto-Polynesian /h/ and /ʔ/.

There a handful of known words (literally—about five) where Māori /w/ comes from Proto-Polynesian /f/ instead of from /w/. Proto-Polynesian /f/ usually becomes Māori /wh/, but sometimes dissimilates to /w/ if there were two /f/s in close succession in the Proto-Polynesian. So if a Māori word has the sequence wah-, it might be from Proto-Polynesian *faf-, instead of *waf- or *was- as you might expect.